NFTs and an Accessible Art World : Fantasy or Reality?

By Riddhi Dastidar | Apr 29 2022 · 15 min read

Low barriers for entry, fewer gatekeepers and long-term financial gain—with NFTs gaining heft in the Indian consciousness, how solid is the promise of a more artist-friendly art world?

“As a 14 year-old with no connection to the art-world, the traditional route would mean I’d need a degree even though I’ve been making generative art for years. Before I got started with NFTs my artworks were exhibited in a regional gallery for at most a week—a 100 people across Chennai including my relatives, would come see them. With NFTs I have a global audience. No one asks about my past. All they care about is the present.”

That’s Laya Mathikshara—a generative and AR (augmented reality) artist-prodigy, who wasn’t allowed to be on social media by her parents until recently. She encapsulates an old conundrum in this new space. With NFTs gaining heft in the Indian consciousness, how solid is the promise of a more accessible, artist-friendly art world?

Web 3.0 and NFTs could signal a new era in India—one where traditional white cube barriers like age, class, caste, gender and more can be transcended. But it’s important to view NFTs as an extension of the digital art space; as an authentication mechanism and not a separate entity. Consequently, some of the limitations of the digital art space apply here too. But there are a lot of potential pros: with the metaverse, artists and buyers alike can technically be located anywhere; the various kinds of capital required to exhibit in galleries can be disrupted as there is no referral process or middlemen for creators to confront on blockchain platforms; digital artists finally have a way to monetise their hitherto intangible work; there is the promise of long-term financial stability from original art for creators, instead of the drudgery of a day-job in corporate design; there’s even the dream of royalties for Indian artists in a market where none previously existed; creators can tap into a dispersed customer base—not just an exclusionary one primed for ‘fine art’. With NFTs, the possibility of upending all the usual barriers glimmers tantalisingly within view, and with a novel sense of immediacy—as crypto-fortunes are built overnight with the whims of the market.

The answer, we find, lies somewhere in the middle, riddled with contradictions and possibilities. For instance, take the phenomenon of lazy minting.

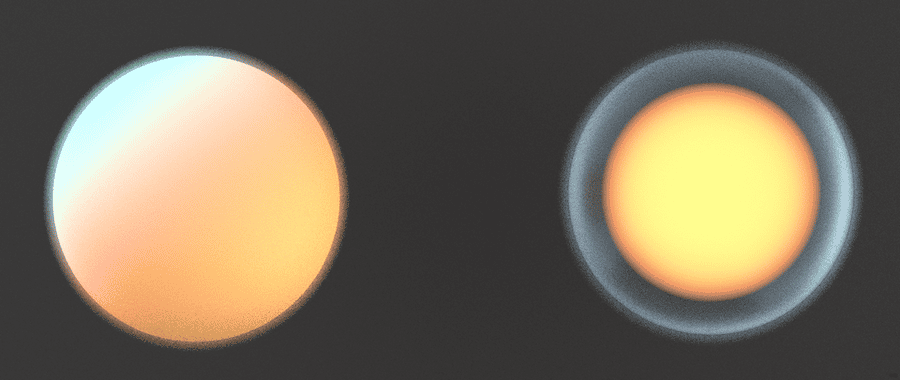

Still of 'Fifth Dimension' series by Laya Mathikshara which depicts a 2D painting seen through a 3D glass sculpture -- art in which neither the painting nor the sculpture can be seen, but is instead a unique combination of the two - the 5D of visual art (2D+3D=5D). Image courtesy the artist.

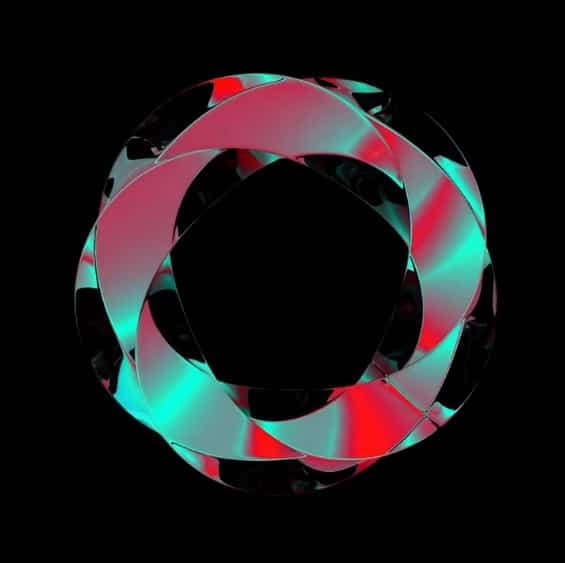

A recent piece Laya Mathikshara created for the famous World of Women PFP collection representing women in tech, ‘Aforest while C++’ which marries 3D cubism with nature images via the Cinema 4D software. Image courtesy of the artist.

The Promise of Low Overheads

Authenticating work as an NFT involves ‘minting’ artwork on a platform by way of ‘gas fees’ that must be paid by creators. Lazy minting, available on some NFT marketplaces such as OpenSea and Terrain.art, rolls the cost of minting into the same transaction that assigns the NFT to a buyer. Thus, theoretically, creators can evade up-front investment unless a sale is made.

For Delhi-based architect-turned artist, Shwetang Pathak, 22, the NFT space means not having to ask his parents for money. “Most Indian parents dislike it jab bachhe bole ki humko artist banna hai. I can evade the art gallery referrals and investment required. Plus the NFT community is so welcoming, I’ve made many contacts who’ve helped get artwork commissioned even outside the NFT space,” he says.

Lazy minting should make this even easier, but on closer examination, the picture that emerges is more complicated. “OpenSea still charges a fee for initiating an account as an artist. Super-exclusive international platforms like Foundation are invite-only, and require you to mint each token yourself,” Pathak says.

Further, the resulting overall cost of a piece being driven up makes sale of a single art piece less lucrative. “The only piece I’ve done with lazy minting remains unsold over a year later,” says graphic designer Tanya Singh who goes by @thedoodlemafia on Instagram. “As the consumer and creator market diversifies and matures, I feel gas fees will go down, and lazy minting won’t be a taboo—kind of like what happened with Netflix in India.”

There are also economies of scale at play here, Mathikshara points out. “For one-on-one sales, it’s comparatively less effective, but if you’re dropping a PFP (profile picture) collection (which tend to be highly popular) you’d usually put up over 1000 pieces where the cost would be dispersed.” An example is a recent piece she created for the famous World of Women PFP collection representing women in tech, ‘Aforest while C++’ which marries 3D cubism with nature images via the Cinema 4D software.

There are ways to get around the single-piece problem, Pathak adds, invoking Patreon’s unlockable tiers system as an example of how to increase value by linking benefits. “With lazy minting, I can make an NFT out of the main artwork and bundle bonus materials like stills, 2k, 4k and 8k versions of videos, work-in-progress and behind the scenes glimpses. These unlockables increase the value of the piece, and act as more concrete proof of work, making it more interesting to buyers. Buying the lazy minted NFT thus gives access to exclusive materials that only the buyer or the owner can have.

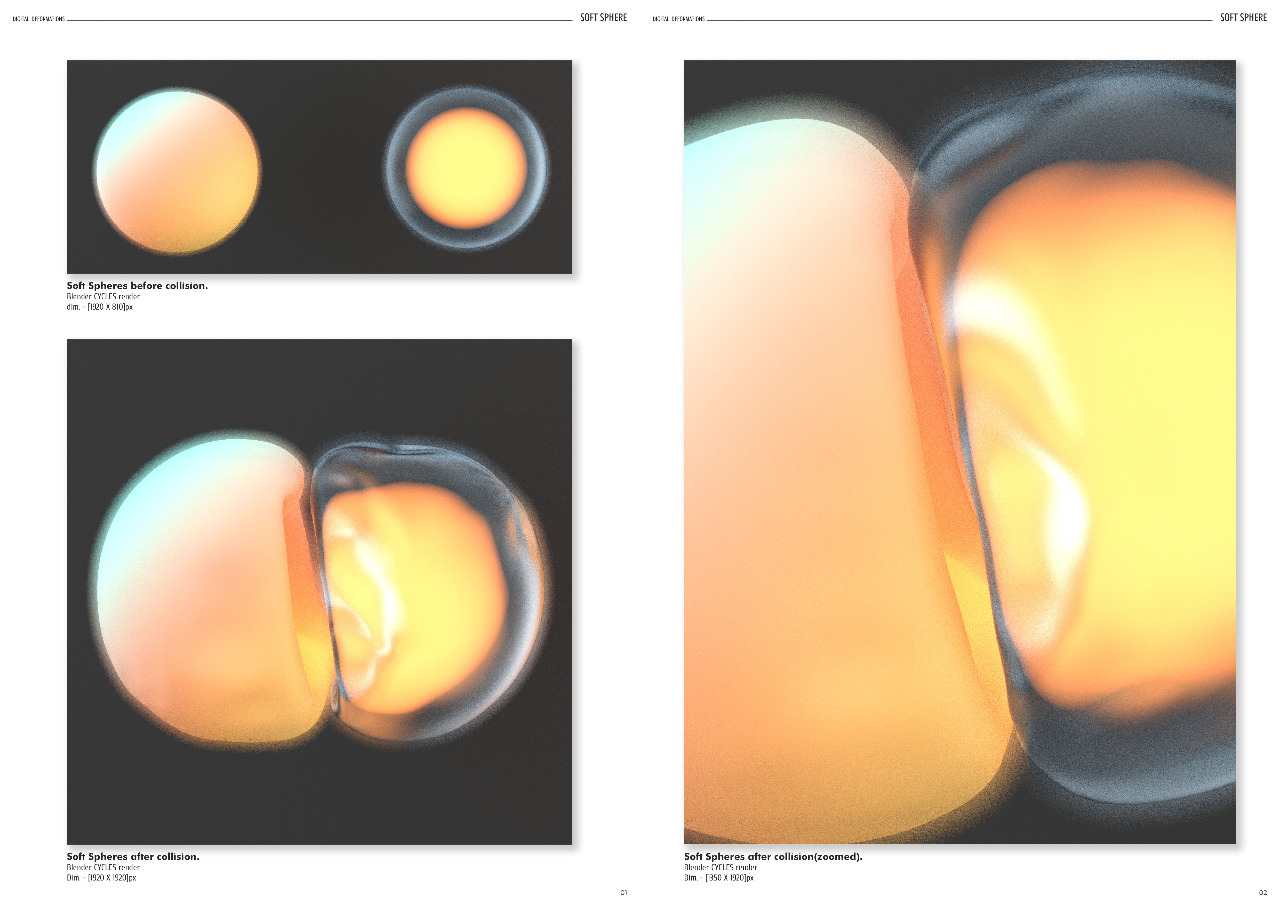

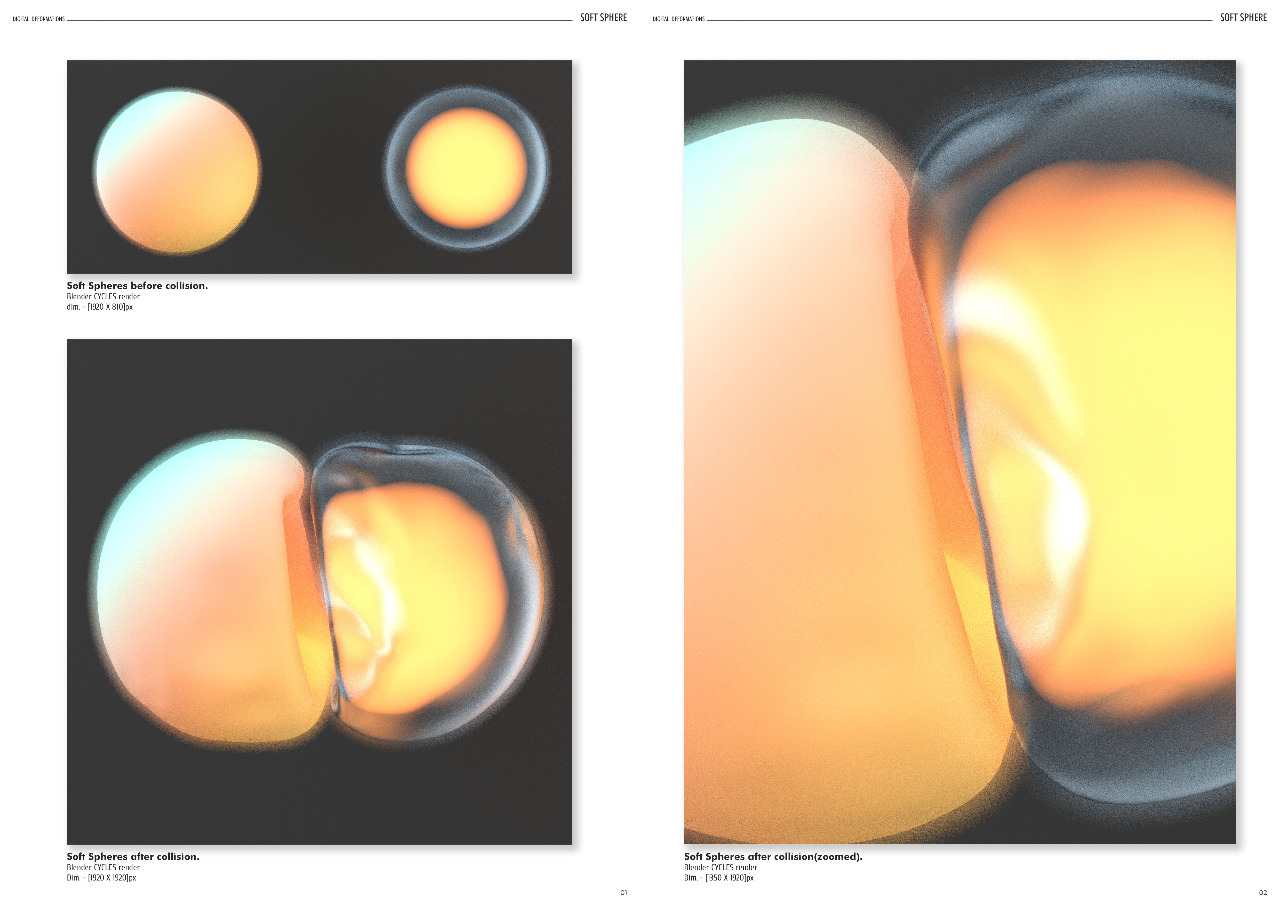

Collisions in Soft Bodies - Spheres in action, part of the Digital Deformations collection by Shwetang Pathak. Image courtesy the artist.

Possible Art-Futures

Pathak draws on his passion for architecture to create digital animations using Blender, an open-source 3D CG software. “Unlike many others, Shwetang’s work actually uses digital media to create things that conceptually make sense as NFTs,” Singh says. “I don’t know if it makes sense to put a static image out there, although I have!” she laughs. Still the NFT space is promising to her, as it is native to a whole new generation of artists who are able to bypass the established system.

There are also more established artists who are keen to explore NFTs for their subversive potential. Among them are Enit María and Srinivas Mangipudi, a Goa-based artist couple from Peru and India whose collaborations have been exhibited at the Art Gallery of the Embassy of Peru, New Delhi, Cultural Equinox Arts Science Festival, Rio de Janeiro, and International du Films sur l’Art Montréal among others. The duo live in Parra, a village on the outskirts of Mapusa, and spoke to us over a fluctuating internet and telephone connection.

The world of NFTs and blockchain was like “second skin” to Mangipudi, who has a background in computers and has been generating paintings from programming code for years. “I’d been looking at ways to interact with the blockchain world more conceptually, rather than NFT’s utility as provenance or as a token of trade.” One such exploration took the form of a public art project, Portrait of a Nation, where the duo and Madhavan Pillai travelled from Kanyakumari to Kargil in 40 days, making people paint collaborative portraits as an inclusive representation of the country. “We intended to create NFTs of each portrait and use the funds to create more public funded art projects. But then the complication arose, how do you actually disburse these funds even if you’re able to generate funding? How do you get public art into the hands of people in non-metro cities?”

This hits at the heart of the issue for Mangipudi—barriers to entry are replicated and the government’s flip flops on blockchain and crypto further discourages new entrants, he says. Even though the premise of NFTs is extremely interesting, these things have a tendency to mutate, muses writer, researcher and curator at Terrain.art, Srinivas Aditya Mopidevi: “It’s important to keep an eye on who the main players are and how it’s going to translate tomorrow. It’s a similar conversation as how the internet translated from being open source to being led by heavily surveilling corporations.”

He adds that Terrain.art tries to level the playing field by linking artists creating interesting work to the NFT space via Terrain Open, their homegrown platform aimed at democratisation. Vadodara-based Andhra painter and print-maker, Kodanda Rao Teppala elaborates via a translator over text: “NFTs and Terrain have hugely increased my reach, taking my images easily to a global audience and giving me some measure of renown. At 42, this has given me a certain hope and courage to keep going. While art is a universal language, being someone who is non-English speaking, this technology has tremendously overcome that barrier.”

Mathikshara adds: “I was totally unknown initially. There are many regional communities on Clubhouse and Twitter spaces like NFT Malayali that emphasise a particular language. English itself isn’t a huge barrier. You just have to actively take part in the community, help others with their engagement too.” She pauses. “Of course if you don’t have an internet connection you can’t make NFTs!”

Art for Whose Sake?

For artists in India, where royalties have not historically existed, NFTs promise recurring returns from artwork. “Because it is recorded on the NFT ledger, 10 percent of sales has to come back to the artist from secondary sales,” says curator Mopidevi. “And the idea of long-term is important for both ends of the market—creating a new collector base as well as a creator base. With Terrain, we’re trying to invite different kinds of creators and not restricting ourselves to fine art or an academic style of art making. In this way we’re moving beyond establishment-led ideas of gatekeeping.”

“In my opinion, NFTs do provide another revenue stream to Indian artists but their viability as a long-term and stable income stream is questionable. There’s a lot of buzz right now regarding NFTs but the space requires more of a deep dive around questions of ownership and exploitation,” says Manojna Yeluri, the founder of Artistik License, an eight year-old legal practice for independent artists in Hyderabad and Bangalore.

Understandably, many artists remain reluctant to dive into the NFT space — even when their work draws heavily on technological interventions, like Bengaluru-based Nihaal Faizal: “I have nothing against more income streams but right now it feels like anything that is digital is being put up as NFTs because it’s trendy. I wouldn’t mind if someone paid me in crypto, but why do I need an NFT as provenance when I have an authenticity certificate anyway? If you look at Seth Siegelaub’s work on artist contracts, resale royalties and certification around conceptual art way back in the 60’s—the questions being asked were very precise: What is the work, why is it this way, what is the market in which it exists, what is the reproduction of the work, or is the work the reproduction?”

Mumbai-based fine artist Shailee Mehta, 24, whose work turns an autobiographical lens on female embodiment and depictions of care and intimacy, says, “It’s not just the NFT space but the digital space at large that democratises the art market. A Gond artist I know who was facing a financial crisis during the pandemic was able to sell almost all his paintings on Whatsapp.”

Overall, Mehta isn’t convinced. “My paintings and drawings aren’t just images to be digitised but art objects that need to be experienced. Where they are shown and what their affective relationship is with their environment, their physical scale and the proximity of the object with the viewer are critical aspects too. There is a presence I like my work to have for the audience that I feel is lost in the digital space.”

Perhaps this feeling lingers in the art world, which could be one reason why a considerable volume of NFTs in India now are physical works that merely use an NFT chip as authentication or why a physical work accompanies the purchase of an NFT in auctions. Thus they retain the benefits of authentication/resale from the NFT marketplace but are still works to be experienced physically.

Yeluri sums it up: “The thing about relying on blockchain tech enabled solutions is that they offer the opportunity for transparency and additional commercial success. But it isn't necessarily guaranteed— which I feel a lot of stakeholders in the creative and cultural industries need more time to dwell on. Many of the existing rules of copyright and contract law extend to NFTs and the truth is that the viability of NFTs as a revenue opportunity for artists relies on factors that are more systemic — accessibility to digital resources, proper legal and business guidance that allows the artists to make informed decisions. I think it offers an exciting array of opportunities, but there's still a long way to go before I'd say without a doubt that it's a guaranteed revenue support solution for artists.”

While the NFT marketplace of art cannot elude the insidious logic of cultural industries, it seems there is still plenty of healthy debate and churn to be had around if and how it will transform artistic practices in India—whether conceptually, or financially, for the better. If it’s only the latter, would it be so unwelcome? After all, ‘art for art’s sake’ has usually been a refrain of the privileged.

Riddhi Dastidar is a Delhi-based writer of fiction and non-fiction. They tweet @gaachburi.